As a test manager, you constantly are looking at what you need in order to carry out the mission of your group. You know that you need several resources to do your job, but when you go to your manager looking for resources, her eye goes immediately to the bottom line. When it appears as if there's no way to make your boss comply with your requests, Esther Derby has a tactic that will help you make your boss see things your way.

You've told your manager that you need an additional server to create a production-like test environment. You also need a new test tool to adequately test a feature and a person with test automation skills to provide frequent feedback on the state of the code.

"We didn't budget for that expenditure," your manager intones and turns away from you to check her email.

Still, you run through the reasons why you need the equipment and the additional staff.

Your boss looks up at you. "Look at the bottom line. This costs too much. You'll just have to be creative and get the work done with what you've got," she says with a note of finality.

So it's time to be creative-not in making do with the resources at hand or making up new numbers. It's time to be creative in refocusing your boss's attention. Below is a six-step process I've used successfully to focus attention on hard-to-count benefits as well as easy-to-see costs.

1. Identify the Proposed Alternative(s)

It's almost always useful to consider at least three alternatives. Even when the first option that comes to mind seems like the best, you'll understand more about it for having delineated more than one approach.

If you've already made a proposal for one course of action and your boss has rebuffed you, identify at least two additional options. You may find another viable option; at the very least you'll show your boss that you are considering alternatives.

2. Determine What Is Important to Your Manager

People are more likely to consider proposals that speak to issues they care about. You may think you already know what is important to your boss—meeting a budget target or a quality standard or sustaining morale, but it's still a good idea to sit down with your manager and ask her. You want to know what's important relative to her issues and what factors would help her make a decision. Let's look at an example drawn from real life.

A VP in an IT organization who is concerned that poor communication between the development groups and the operations folks is leading to production problems when the developers release new features to production. You've done an experiment with a pre-production turn over meeting, but she's skeptical that it will help.

When you ask her what's most important to her, she might say that the most important things to improving communication between her development and operations groups are avoiding production problems, limiting disruption to business, and taking a proactive stance rather than reacting to problems.

3. Ask Your Manager Who She Considers to Be a Credible Source

Quoting an expert whom your boss believes is a bozo won't help your cause. You need to know who your manager believes is credible-whom she would listen to regarding your case. (If there's no one she'd believe, that's another problem.)

Ask your boss to list these credible people and share with her that you intend to interview them. Don't lock yourself into interviewing the complete list or specific people on the list. Here's why: if for some reason you are unable to interview everyone on that list, or some of the people on the list are unavailable, you leave an opening for your manager to dismiss your analysis.

4. Create a Short Interview Protocol

Outline a short questionnaire—about four to six questions-and use them to guide your interviews. Frame your questions to elicit information about the factors your boss cares about.

To make the case for a pre-production turnover meeting for the VP who wants to avoid production problems and take a proactive stance, you might ask questions like this:

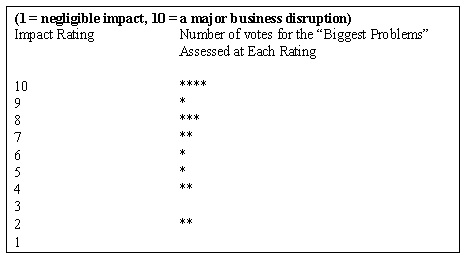

- What issues that cause production problems were a result of miscommunications or misunderstandings between the development group and the operations group? Give your assessment of the impact of the single biggest problem on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 negligible impact; 10 a major disruption to business).

- Which of those could have been discovered before the new features went into production?

You can ask free form questions to follow up on interesting answers as well. 5. Interview Your List of Credible Sources

Keep your interviews short, and record responses carefully. Make sure to account for all the people on the "credible sources" list, even if you were unable to interview them. Otherwise, your manager may assume you were selective in your interviews to bias the case in your favor.

6. Summarize and Present the Results

Write a summary report no longer than one page. Start by reminding your manager that she agreed to the list of people, so the report is at her request. Account for all the people on your manager's list, even if for some reason you didn't interview them. Be sure not to omit negative results. Chances are good that your boss will learn of the negative result anyway, and if she hears it from someone else, your credibility is dead. If you show the negative results, it telegraphs that your case is strong. Explain the negative results, but don't dismiss them or argue them away. After all, your manager identified this person as credible, and it won't help to tell her otherwise.

|

Have the detailed data at hand so you can go over the details if your manager asks for them.

Here are the some of the results from the interviews for the pre-production turnover meeting, which was presented to the VP who wanted to avoid production problems. The interviewer asked the questions listed in Step four. She interviewed sixteen people, each of whom identified the single biggest problem found in a pre-production turnover meeting and then rated the impact of that problem on a scale of 1-10.

This represents each persons' assessment of only the biggest problems, so it's a subset of all the problems. Four people assessed the impact of the biggest problem at 10. One person assessed the impact of the biggest problem as 9, and so forth. For the most part, the development folks identified lower impact problems and the operations folks higher impact problems. (Very interesting!)

This was enough information for the VP to continue the pre-production turnover meeting. "Hold on," you may say. "This isn't hard data. These responses are correlated to any standard of severity." That's true. But the data is related to what the manager said was important to her. And that's what matters when you are building a case.

Acknowledgements: I originally learned this technique from Jerry Weinberg. You can read more about subjective impact analysis in QSM, Volume 2.