Making user stories small is hard. I recently ran a story-writing session with a team and their clients. We brainstormed a dozen stories and then prioritized them. We took the top one and talked about how we could make it smaller and simpler. I knew little about the system and the background, so I asked some obvious questions and challenged everything. I bet I was a pain.

The first cut started with an and. The card said “real time and historical reports.” Whenever you see and, or, either, or but, look to split the card.

Fortunately, everyone in this meeting was open to splitting the stories. After awhile we had a multitude of stories derived from the first one.

Looking beyond Stories

Some teams only work with stories. Their stories make sense to the business and to the technical team, are deliverable quickly—a few days at most—and have value. This is probably the ideal situation, but it doesn’t work every time, and it can be difficult when a team is new to agile.

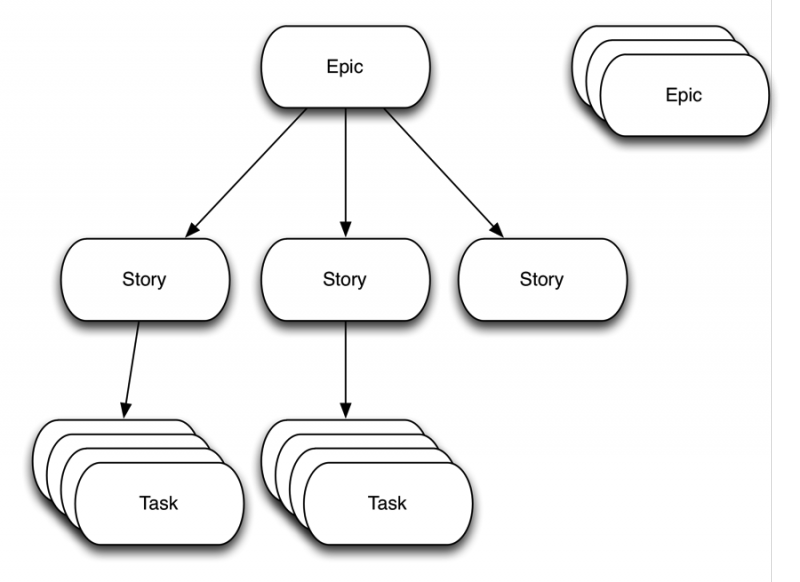

An alternative is to add epics and tasks. An epic is some big piece of functionality the business wants that is delivered via multiple smaller stories. Epics, by definition, break the rule that stories must be small, but they have the most business benefit. Tasks are smaller work items that build a story. They usually can be accomplished in a day or so, but by themselves they are devoid of business benefit.

Go Large with Epics

Sometimes, the business doesn’t want something small; it wants something big! Indeed, it might want more than one big thing. An epic might represent a milestone or notable delivery, or an epic can be a placeholder, something to break down into smaller pieces in future.

It makes sense to use the user story “As a …” format for epics, but there is no law that says you must. Just remember that who, what, and why are useful things to know.

Go Small with Tasks

On the other hand, it sometimes makes sense to break a story down into the work that needs to be done. In calling out the tasks needed to build a story, the development team engages in an act of shared design. Tasks are not normally written in user story format. Instead, they are written by the team, for the team, so use language the team will understand.

A task is a piece of work that needs doing, usually in order to build toward a bigger story. As such, it does not have independent deliverable functionality or generate business value, and, unlike a story, it normally is not a vertical (end-to-end) slice. Most tasks tend to be for programmers, but they could be for anyone on the team.

Not all stories get broken down into tasks. Breaking a story down is an act of design, so whether a breakdown is required or not depends on existing knowledge, the technologies under development, the architecture, and, most of all, the size of the story to start with.

Tasks are useful because they allow the technical team to call out discrete pieces of work without pretending they mean something to the business. Having the whole team examine a story, especially when that brings different points of view, opens up the story. Different team members see different ways of breaking a story down, either as tasks or as smaller stories.

Three Organizational Levels

When I used to run teams, I found that two levels were enough: stories and tasks. However, I regularly meet teams who use epics and stories and seldom, if ever, do tasks. Just because there are multiple organizational levels, don’t feel you have to use all three. If you only need two, good, and if you only need one, then better still.

Avoid the temptation to introduce more levels. Adding levels increases administration and gets more confusing. When you are using an electronic tool, hierarchies can get complicated quickly, and extra complications distract from the real goal. So avoid tertiary epics, intermediate stories, subtasks, and the other names given to additional layers. Whenever I see teams who have added to the hierarchy, the effort and complications introduced are greater than the benefit. If you feel the need to group several stories, remember that you can do this without a hierarchy. Paper clips work well!

That being said, epics and tasks sometimes go by other names, especially natively within tools. Tasks can be called subtasks, stories sometimes go by features, and epics can go by themes. Some teams like to organize their work around user activities, which may be stories, epics, or something else.

If your team, organization, or tool wants to use different language, that’s fine; names are not important. Just ensure that your entire teams understand what is meant by each term, use the terms consistently, and stick to three or fewer levels.

Color Coding and Planning

I like to code tasks by putting them on white cards. That makes obvious what they are. I use blue cards for stories—you might say “Blue is for business.” I’ll also use blue for epics sometimes, but epics seldom make it to the board. Epics are big things, and for a team working in the small, the focus should be on getting the small things done.

These three levels line up well with planning: White tasks are for now and the iteration that is about to happen, and they are mainly for the team. Blue stories are what the product owner is lining up for the near-term iterations, and epics are for the future. Epics touch on strategy and may even be beyond the product owner.

Making Use of Your Choices

Being able to choose among stories, epics, and tasks brings flexibility to an agile team, but don’t think you must use epics and tasks. Sometimes when stories are decomposed into multiple smaller stories, each stands on its own and no hierarchy is needed. When a story is really small, knowing what needs doing can be trivial. Having a clear understanding of the differences between each level and knowing what size story to use for each situation will improve the accuracy of your sprint planning.

User Comments

Yes, I an imagine that working

Pages