When we deliver software products, we need to be able to tell our customers what they're getting. Not just product documentation, but specifically, every time we deliver a new release, what problems were fixed, and also what the new features are. If the software is subject to periodic audits, we need to tell them even more, especially the ability to trace a requirement or change request to what was changed.

We do that very well. We point to the build that the customer currently has and to the build that we're planning on shipping to the customer. We then ask for a list of problems fixed, a list of the new features, and any documentation available for the new features. In a few seconds we have our answer in a simple release notes document ready for the technical writer to spruce up.

This is good and useful. For many shops this might be a leap forward, but in the context of an ALM solution, it doesn't go far enough.

If my world is limited to taking a list of problems and features and fixing/implementing them and delivering builds with those implementations, the above release notes are helpful. However if, instead, my world deals with taking a requirements specification, which is changing over time, and then ensuring that a conforming product can be demonstrated to the customer, my world is a bit bigger. If those requirements also include a budget and delivery schedule, it's all the bigger. Then if I happen to have one of those management structures that want to know the status of development, including, whether or not we'll meet our requirements within budget and on time, it's bigger still. If I have to track what customers have which problems and feature requests outstanding with each delivery, it's even bigger.

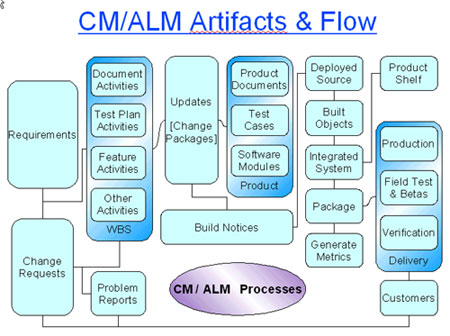

Many customers ask for much more than release notes. They want to know about their outstanding requests. They want to know about the quality level of the software we're shipping them. They want to know about the risks involved. They want to review the product specs before development is complete so that they may have additional input on the functionality. They want to know if our delivery schedule will be on time. We need a virtual maze of data to track the information involved in the ALM process (see diagram) and to support the audit process.

Traceability and Auditability

Traceability and Auditability

Traceability is the ability to look both at why something happened and the impact a request has on what had to happen. It's a two way street that allows me to navigate through the inputs and outputs of my process. Auditability allows me to use the traceability to ensure that the requirements/requests have been met and to identify those non-conformances/deviations in the delivered product.

Traceability requires the providing of both the linkage structure and the data which ties one piece of data to another. At the simplest level, every time a change is done, the change (itself a first level object) is linked to the reason for the change (typically a problem report or a feature activity). In a requirements-driven process, each customer requirement is traced to/from a product requirement, which is traced to/from a design requirement which is traced to/from the source code change. In other shops, product requirements are traced to/from feature activities which are part of the WBS, and these are traced to/from the source code change.

The traceability means that I can go to the file revision and look at the change that produced it (another traceability step) and, from there, identify why the change was made, to see why the file revision was created.

If we look at the V-model of development, the downward left side of the V deals with this development process, from requirements down to code. The upward right side of the V deals with building and testing. Again, it is important for the traceability linkages to continue both up the V and across to the left side. However, when we also include the actual test results (as opposed to just the test suites) on the right side, we now hav specific identification of which requirements on the left side were verified as met by test results on the right side. This is, in software, the key component of the functional configuration audit (FCA) as it verifies that the as-built product conforms to (or fails to conform to) the set of requirements.

With appropriate tools and architecture, it is also possible to embed the specific file revision identifiers and even the build tool revisions into the executables to help with physical configuration audit (PCA), such as it may be for software.

Traceability

Where do I need traceability? Quite frankly, trace whatever can be traced. Who did something? When? Under what authority? How was that verified? When and by whom? In what context? Here's a handful of things we like to track:

- What files were modified as part of a change or update? We use the term update here to indicate that a single person has performed all the changes?

- Which problem(s) and/or feature(s) were being addressed as part of the update?

- Which requirement or feature specification does each problem refer to?

- Which requirement does each feature specification correspond to?

- Which requirements were changed/added as a result of each feature request?

- Which customers made each feature request or problem fix request?

- Which baseline is a build based on? Which updates have been added to the baseline to produce the unique build?

- Which requirements are covered by which test cases? Which ones have no test case coverage?

- Which test cases were run against each build? Which ones passed? Which ones failed?

- How much time does each team member spend on each feature?

- Which features belong to which projects?

- Dependencies between features and between changes.

This is just a partial list. But it's sufficient to give some examples of the benefits of traceability.

Build Content

One of the most common queries in our shop is, "What went into a build?" This may seem like an innocent question, or to some who know better, it may seem like a terribly complex question. When we ask what went into a build, we ask these questions:

- What problems were fixed?

- What problems are outstanding?

- What features have been added?

- What requirements have been met?

- Which updates (i.e., change packages) went into the build?

- Which files were changed?

- How have run-time data configuration files changed?

Why is this so common a query in our shop? Well, first of all, our ALM toolset makes it easy to do. Secondly, when something goes wrong, we want to isolate the cause as quickly as possibly.

If a new delivery to a customer introduces a problem they didn't previously have, we ask: What changes went into this build as compared to the customer's previous release build? We then screen these based on the problem and more times than not isolate the cause quickly. Even more frequently, if the system integration team, or verification team, finds a problem with an internal build, we go through the same process and isolate the cause quickly.

By having a sufficiently agile development environment that packages a couple of dozen or so updates into each successive build, we're able to pinpoint new problems and hopefully turn them around in a few minutes to a few hours. Finally, we need to produce release notes for our customers. This type of query is the raw data needed by the technical writer to produce release notes. It's also the raw data needed by our sales team to let prospects know what's in the new release, or what's coming down the pipe.

Customer Requests

Customer requests provide useful input. In fact we find that customer input in a real world scenario is generally superior to the input gathered through other means for what should go into the next release of the product.

But managing customer requests is not a trivial task. Each customer request is traced to one or more features or problem reports. These in turn reference the product requirements from which they stem. Each development update must be traced to one or more problem reports or features. Each build is traced to a baseline and a set of updates applied to that baseline. Each test case is traced to the requirement(s) it addresses and each test run is traced to both the build being used for testing and the set of test cases that apply, and for each, whether they have passed, failed or not been run.

The traceability information allows the process to automatically update status information. When an update is checked in, the problem/feature state may advance. When a build is created and integration tested successfully, the problem/feature states may again advance, but so do the corresponding requests (possibly from multiple customers or internal) which have spawned the problems/features. When specific feature/problem tests are run against a build, the related requirements, features and problems are updated, as are the related requests. And this happens again when the build is delivered to the field and promoted to an in-service state.

Now with all of these states updated, it is a fairly trivial matter to produce, for each customer, a report that tells each customer the status of each request including clear identification of which ones have been implemented, verified, or delivered, as well as those which are still to be addressed. Customers appreciate this by-product of traceability.

Project Status

A project is sometimes defined as a series of activities/tasks which transform a product from one release to another. In a more agile environment, a project might be split up into quite a few stepping stones. The tasks include feature development, problem fixes, build and integration tasks, documentation tasks and verification tasks.

If these tasks are traced back to the rest of the management data, it becomes a straightforward task for project management and CM/ALM to work together. Ideally, the features assigned to developers for implementation are the same object as the feature tasks/activities which form part of the work breakdown structure (WBS) of the project management data (see my June 2007 article).

This traceability makes it easy to identify each checkpoint of an activity, allowing accurate roll-up of project status, even without the detailed scheduling that is less present in a proirity-driven agile environment. In our shop, we go one step further and tie in the time sheets directly to the ALM tasks, again within the same tool. This allows for automatic roll-up of actual efforts, which in turn gives us better data on how well we did for planning the next time around, in addition to helping with risk identification and management.

Traceability allows this flow of status information to proceed. In some tools, this is a trivial task (especially if all of the component management functions are integrated into a single repository), while in others it is less trivial and requires some inter-tool glue. But it's the traceability that permits the automation of the function.

Auditability

Auditing is the task of verifying that what you claim is accurate. If you claim that a product has certain features, a functional audit will verify that the product does indeed have those features. If you claim that a product will fits a particular footprint, a physical audit will verify this.

In software, there is a focus more on the functional configuration audit than the physical configuration audit. The reason for this is that software is a logical, not a physical object. Still on the physical side of things, you may want to audit that the file revisions that are claimed to be in the executable are indeed in the executable, and that the versions of the tools used to produce the executable were indeed used. This involves a bit of process and a means of automatic insertion of actual revision information into the software executeables, as well as a means of extracting and displaying this information. Sometimes, the process that automatically inserts this information is audited to ensure its accuracy.

Similarly, for functional audits, the process used to generate and record the information to be used by the audit needs auditing itself. For example, how does the process that creates test cases for a requirement or set of requirements ensure that the test case coverage for the requirement is complete? Given that one can vouch for its completeness, it then remains a relatively simple task to ensure that each requirement, or if you like, each requirement sub-tree, is covered by test cases. In CM+, for example, you would right-click on a portion of the requirements tree and select "missing test cases". Any requirements missing test case coverage are presented.

Making sure you have test case coverage is just one part of the audit. You also have to make sure that the test cases were run, and identify the results of the test cases. The passed test cases exercised against the particular build (i.e., identified set of deliverables) identify the functionality that has been successfully verified.

What Does It Cost

Traceability seems like a lot of extra effort. Does the payback justify the effort?

First of all, cost is irrelevant if the traceability data is incomplete or invalid. Here's where tools are important. Most of your traceability data should be captured as a by-product of efficient everyday processes. A checkout operation should have an update (i.e., change package) specified against it. A new update should be created by a developer from his/her to-do list of assigned problems/features by right-clicking and selecting an implement operation. Problem reports should be generated in a simple action applied to the customer request, to which it would then be linked. It is important that your processes are defined such that all the necessary data is collected.

A good object-oriented interface can really make the process effortless, or even better! Traceability data should be generated wherever an action on one object is causing a new object to be created, or whenever an action on two objects specifies some common link between them.

The developer has to check out a file to change it, so why not select a current update from his list to give the change some context and to help in branch automation, with a by-product of traceability. It sure beats typing in a reason for the checkout or having to enter a problem number or task number, possibly foreign to the version control repository. It also means that down the road, the developer does not have to supply any missing information.

Still if you do not have a good starting architecture and toolset, the effort to support your process effectively, while gathering traceability information, could be painful and costly. Make sure you start with a flexible toolset which will let you change the data and processes to meet your requirements. Also make sure that you can customize the user interface sufficiently to cause your team members the least grief and the greatest payback.

In the end, your customers will be satisfied. Your team members will also be satisfied and you'll end up with better product.