Johanna Rothman received a variety of responses to her recent writing on agile architecture. In this article, she attempts to clarify her case for having an architect on some—but not all—agile programs, depending on a number of factors.

I’ve been blogging about agile architecture, and the responses have been fascinating. Some people are totally against the idea of an agile architect, regardless of the size of the program. Others are ready to give me the benefit of the doubt. In this column, let me clarify the case for (or against) the job-titled agile architect.

As with all interesting questions, the only correct answer is “It depends.” It depends on the size of your program, how architecturally complex the product is, the desired speed of release, how long you have been practicing agile, how much technical debt you have, and how distributed your program is.

Programs Are Different from Projects

A project is a unique and novel effort, characterized by risk. It has a beginning and an end. A program is the organizational coordination of several projects’ results into one deliverable, which has value to the organization. So, while each project has its own risk, the program has the strategic risk for the organization.

Programs may continue for several releases of the product or system. Programs are large, and one thing we know about software is that it does not linearly scale. What works for a small project or for one team does not work for eight, twenty-five, or forty-two teams.

Program Size Is a Factor

One factor in considering whether you need a formal architecture role on your program is the program size. How many total people do you have? The reason to consider the total number of people is because of the communication paths in the teams and among the teams.

Assume you have seven-person teams. We know that the communication paths inside a team are (N*N-N)/2 which works out to twenty-one paths for a seven-person team. If you have two or three teams, the teams may still be able to build informal communication paths among themselves to share architectural knowledge.

Once you have four to seven teams, you are at the hairy edge of what teams can do informally. I have seen several programs work successfully without a formal architect role and one spectacular failure. I have seen two programs work successfully with three architects participating on feature teams and as architects on the programs. Clearly, your mileage will vary.

On programs with eight teams or more, I strongly suggest you have an architect team, who participate both as part of the feature teams and as architects. Agile architects write code, test, and look ahead just a little to smooth the way for the feature teams.

How Complex Is Your Product

Organizations normally use programs to create “complex” products in the sense that the technical team has more or less opportunity to refactor as they develop the product. (Product complexity might not be the right term here, but it’s the best term I have right now. Let me know what term you would use in the comments below.) Within that notion, there are more-complex and less-complex products. That complexity allows you to make architectural decisions more often or less often.

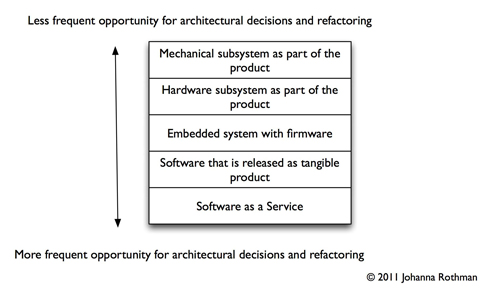

Figure 1 shows one way you might think about product complexity and product type.

Figure 1: Product complexity and opportunity to rearchitect and refactorYou have the opportunity to make many more architectural decisions and refactor much more often when you have a software-as-a-service product than when you have hardware as part of the product. Can you still change the architecture with hardware or mechanical systems? Of course you can. Do you have to coordinate with many more people? Yes. Do you have longer feedback loops? It’s much more likely that you do. Does that mean you should rearchitect less often? Not necessarily. It means you need to coordinate differently, which is why you might need someone—or a team of people—whose job is to manage the risks of architecting the product and to maintain the business value of the architecture.

How Quickly Does the Organization Want You to Release?

Many organizations want to substitute people for time. We all know that nine women cannot create a baby in one month, but somehow, our managers still think we can add many more people to a program and finish the software faster. Assuming you are organized in feature teams, there is some truth to this.

Again, if the organization wants you to substitute the natural evolution of the product for speed, the best way to do that is to have people whose job is specifically to steward the architecture of the system as they create features. Architects can scout ahead and discover the dead ends a little in advance of the feature teams, so the feature teams don’t have to waste their time going down known bad paths. Or, the feature teams can help evaluate prototypes with the architects, but at least everyone knows they are prototypes.

How Long Have You Been Agile?

I wish I could tell you that all organizations start their agile efforts with a small pilot project and move to more small projects. But, several organizations start with large programs, thinking they will just transition to agile in one giant leap.

Agile is a cultural change. You move from a top-down, manager-led approach to a team-led approach to work. Even with my advocacy for architects on large programs, I am not suggesting a separate architecture team—I am suggesting architects embedded on feature teams, who do the hard work of making features function, refactoring, and living with the architecture and the code they build.

Cultural change is slow. Rarely does any large program move from one approach to another with a management mandate—especially if managers continue to command, “Thou shalt be agile.”

I worked with one large program where developer after developer said almost the same words to me: “I haven’t been able to estimate my own work for the past five years. Now, I’m supposed to take responsibility for the architecture? I don’t think so. I make one mistake, and I bet I’m out of here.”

People don’t believe they have the responsibility to take care of the architecture at the beginning of their agile journeys, and they must experiment and prove it to themselves. Having an encouraging architect who is a steward and a change agent—someone who is more of a coach—would help with that effort.

How Much Technical Debt Do You Have?

You likely have technical debt, especially if you are newer to agile and have a legacy product. Many large programs have technical debt in their ability to build and release quickly and in their test automation.

I once worked with an organization that had a fifteen-person build team that took about two weeks to build the entire system. When I explained that they needed to work themselves out of a job and make the build run inside of an hour so that they could become two feature teams, I thought one of those folks would have a heart attack. The build team literally could not see a way to change how the system was built.

But, they decided to try. First, they broke the dependencies so they could parallelize the build on multiple machines. Then, they could address the deeper architectural issues for the build.

It took them months to change the build system to be able to build in under a week. It took another six months to get the build down to two days, but by then, they only needed five people to build. Now, they had ten people available to rearchitect the entire build system so it could take one hour. When I last checked, they were down to six hours without needing anyone to babysit the build, and they still had some work to do.

I also see a lot of technical debt in test automation. If you have a large program, you must have automated regression tests, as well as exploratory tests. You don’t have the time to run lots of manual tests every two weeks.

One of the problems I’ve seen is that the testers wait for the perfect test automation system. I have never seen one perfect test automation system, just as I have never seen one perfect framework for a system. That’s why we need test architects, as well as development architects. Different kinds of testing require different kinds of test automation and different kinds of test automation systems.

The way I like to develop test automation is to build something small, see if it works, and refactor it as I proceed. Now, I’m no architect. I am sure there is a better way to do this, which is why I like to pair every so often with an architect who will say, “JR, if you do it this way, it will be 1,000 times faster.”How Distributed Is Your Program?

The more distributed the program—that is, the more sites involved—the more you need people to communicate with each other about the architecture, the lower-level design, and how the whole system works together. And, the more distributed the program, the more difficult it is to have those conversations. If you have an architect on a feature team or an architect for a few feature teams, those conversations are more likely to occur, because that person is responsible for them.

Do You Need a Defined Agile Architect

I hope you still think the answer is, “It depends.” Maybe it even depends on more factors than I’ve discussed here. Consider how you can use agile architects to create more ease for everyone in your program and reduce technical risk if:

- You have a program of more than three teams, with fewer opportunities to make decisions about architecture and refactoring and with more pressure for an earlier release date or lots of people

- You are early in your agile transformation

- You have more technical debt than you would like

- You have a distributed program

Your program manager, developers, and testers will thank you.

User Comments

One way to focus on architecture is to consider system requirements, as suggested by Julian Browne http://www.julianbrowne.com/article/viewer/systemic-requirements and of course Tom Gilb http://www.gilb.com/tiki-download_file.php?fileId=47

We need to be aware that design choices can end up being an "architecture by default". When we are aware of this, and can act to make a difference, we contribute to better systems - whatever our job titles.